Rachel Joselson brings "Songs of the Holocaust" to life

Collaborators include Réne Lecuona, Scott Conklin, and Hannah Holman

"Sweet child, sleep.

The little sun makes the eyes close.

Little hidden birds sing,

Moon face bright shows itself,

All here unites. Soft quietness shines.”

--Ilse Weber, “Wiegala” (“Lullaby”)

trans. Rachel Joselson

Composed of gentle imagery and nurturing affection, the song sounds and reads like a typical lullaby, designed to calm children into repose. But Ilse Weber’s “Wiegala” (translated to “Lullaby”) has a much darker history.

Weber wrote the song while imprisoned in Theresienstadt (Terezin), a Nazi concentration camp, during the Holocaust. Tasked with caring for Terezin’s children, she composed music to help comfort them under the camp’s severe living conditions.

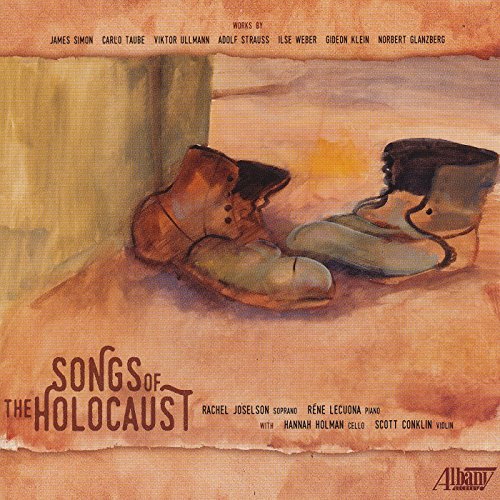

In a new University of Iowa project, “The Songs of the Holocaust,” Music professor and soprano Rachel Joselson revives music composed by Terezin inmates. Joselson collaborated with pianist Réne Lecuona, also a professor in the School of Music, part of the College of Liberal Arts & Sciences. Violinist and UI associate professor Scott Conklin contributed on a song, and cellist and former School of Music lecturer Hannah Holman played on a song as well.

The project began when Joselson, who is herself of Jewish heritage, heard a recording of a few songs composed at Terezin. Intrigued, she began to search for other works that were rarely or not yet recorded.

“When I found out that there is a vast repertoire created in the camps, composed and performed under the most inhumane living conditions, I was fascinated to know more,” she said.

She got in touch with colleagues in Germany and Israel, who sent her scans of unpublished or out-of-print music. The United States Holocaust Memorial Museum proved a valuable resource as well. Over a year’s time, Joselson and collaborators created the CD.

University of Iowa History Professor Lisa Heineman—a scholar of 20th century Germany and the Holocaust whose own grandparents were interned at Terezin—said the camp had a particularly high number of artists and musicians, in part because of the population there. Many of the inmates were Czech Jews with advanced education, which typically included some training in music or art.

Due to the rich cultural knowledge and skill present at Terezin, it lent itself well to being a “model” camp. The Nazis used Terezin to demonstrate to the world that conditions at concentration camps were fair. Faced with international pressure, German authorities invited the Red Cross to take a tour of Terezin. To prepare, they deported the oldest, sickest inmates, and spruced up the facilities with fresh paint and signage. The authorities then staged a tour, leading the Red Cross down an approved path within the camp—which included a concert by Terezin’s orchestra. The Red Cross left to write a positive report about Terezin’s conditions.

Terezin was not a “death camp” with organized killing facilities, but over 33,000 people died from the living conditions. Of the 150,000 Jews sent there, over 84,000 were deported to their murders in other camps’ gas chambers. It primarily served as a transit camp, a way to organize Jews on their way to being systematically killed elsewhere.

Those imprisoned might never know when a deportation was coming, leaving inmates in constant fear of being called on the transport list.

"A narrow note with green stripes,

To whom will it be read? Whom will it grab?

Am I one of them? Am I not one of them?

Passed over this time, the victims are three.

Three from our room alone,

There the transport will be over a thousand.

Into the dark, into misery? Where will it go?

Will we see our children there?"

--Gerty Spieß, “Transport”

The dire conditions of the camp and the deportations provided significant challenges for the musicians. For instance, on the eve of a performance, a large portion of the orchestra might be deported, Heineman said.

Nonetheless, the Nazis allowed the performances, partly to use as propaganda or as evidence of humane conditions, such as with the Red Cross—but also likely because they viewed the concerts as harmless music made by elderly Jews, and not worth the effort of disallowing them.

Terezin’s musicians were prolific, composing hundreds of pieces. Though used as Nazi propaganda, music still provided those in the camp a tool to cope.

In a 1989 interview, quoted in the CD’s insert booklet, Terezin survivor and composer Paul Kling said, “It was survival…Culture is a survival mechanism, unified in spirit.”

This was a common sentiment, according to the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum.

“For many victims of Nazi brutality, music was an important means of preserving and asserting their humanity,” reads the web description of the museum’s Music of the Holocaust collection. The description notes that much of the period’s music was composed at concentration camps, particularly at Terezin.

Many of the songs’ lyrics convey a feeling of loss, and some strive toward hope.

"Promise me one thing, I know that times will come

They will be darker than all that came before

[…]

Through deep of night will I then go to you.

On tired soles and in all desperation

[…]

Promise me one thing, you will give a sign

That for me, the gate of the gloomy night opens"

--Ernst Münziger, “Versprich mir eins” (“Promise me one thing”)

University performance of "Songs of the Holocaust." (Rachel

Joselson on far right, Réne Lecuona third from right.)

The result is an emotional experience for both performers and audience members, Joselson said.

“At our first presentation here in Coralville at my synagogue’s Holocaust commemoration concert, I couldn’t get through several pieces without tissues and a couple of interruptions,” said Joselson, who is fluent in German and completed translations for the CD herself. “Many in my audiences are children of Holocaust survivors, and children who survived but lost their families. These people are grateful and enriched by the experience.”

Nine Holocaust survivors—some of the last living survivors worldwide—attended a performance at Montclair State University in New Jersey. The chair of the university’s Department of Religion presented biographical tributes to each survivor before the music began.

One song, “Für Ule,” is sung from the point of view of a father who realizes he will not be able to raise his child.

"My darling son, my later happiness,

I leave you fatherless behind.

An entire nation is not enough;

Humanity will be your father.

My dear son, my little light,

You are faraway. I can’t see you."

--Adam Kuckhoff, “Für Ule” (“For Ule”)

Lecuona, the CD’s pianist, said “Für Ule” was particularly moving to record.

“It taps into some sort of universal truth, to want to protect your children—and to not be able to protect them as you faced the Nazi regime would be just unbearable,” she said. “We recorded around the time of the establishment of the Islamic State. Those parents aren’t able to protect [their children], either. So it kind of ties into human rights conversations right now.”

The performers’ work on the CD has met much critical acclaim.

“[Joselson] is closely attuned to all of these songs, singing with a clean, strong soprano; Réne Lecuona contributes bright, vibrant pianism, almost as enchanting as that of her famous namesake,” reads a Fanfare review. “The recorded sound is exemplary.”

And critic Erin Heisel, in American Record Guide, wrote: “Joselson sings with legato and excellent diction, and Lecuona’s playing is supportive and clear. Conklin and Holman add warmth and depth.”

The musicians will perform the music of “The Songs of the Holocaust” at colleges, universities, and religious and human rights organizations for years to come, tying the University of Iowa and the state of Iowa with the important work done with the project. They will also perform at the United Nations for the General Assembly on Jan. 27, when the UN will commemorate victims of the Holocaust.

“There’s something about the sound of a human voice creating beauty and doing no harm that is very healing and even redemptive,” Lecuona said. “I believe in this project for two reasons: first, that it keeps the reality of what happened in our human consciousness, and because the creation of beauty is one of the best antidotes to evil in the world and in ourselves.”

“Cuddle your little head in my arms.

With mother one sleeps cozy and warm.

Sleep, overnight a lot can happen.

Overnight can all worry vanish.

My child, you will see, once you are awake,

Peace arrived overnight.”

--Ilse Weber, “Kleines Wiegenlied” (“Little Lullaby”)

-- Story by Nora Heaton